[PT] “Our Feet Claim The Ground” – Caminhar como Forma de Entender e Agir na e com a Cidade * [ENG]“Our Feet Claim The Ground” – Walking as a Means to Understand and Act In and With the City [PT]

August 7, 2016 § Leave a comment

[PT]

Fig. 1 – Eadweard Muybridge [1]

- Introdução

Numa altura em que a questão da mobilidade urbana volta a ser debatida pelos decisores e gestores das cidades, com vista a uma melhoria da qualidade do ar das grandes urbes, de um esforço de requalificação dos espaços públicos, para usufruto dos cidadãos e de uma tentativa de melhoramento e do poder de atração do parque habitacional dos centros urbanos, reequaciona-se a capacidade que a introdução de mobilidades suaves tem, na resolução dessas questões. Surge assim a possibilidade de olhar para o peão e para o andar urbano, como forma de mobilidade e como solução prática, simples e eficaz para a resolução de alguns dos problemas das cidades, bem como elemento-chave para o planeamento urbano e para o aumento da qualidade de vida dos cidadãos.

2. A Cidade e o Automóvel

A revolução tecnológica iniciada no século XIX com a invenção da máquina a vapor, foi inquestionavelmente responsável por uma alteração profunda na sociedade, com consequências diretas a nível económico, social e cultural. O que começou por ser uma mudança nos métodos de produção de bens, na imagem das paisagens rurais e urbanas (devida em grande parte à industrialização e ao êxodo rural para as cidades), depressa se transformou numa alteração profunda na forma como o Homem interage e se integra com e no território, como nele se desloca e como essa deslocação o faz percecioná-lo de uma forma diferente.

Ao longo do século XX, e enraizada numa profunda convicção e crença nas capacidades e benefícios que a revolução na mobilidade podia produzir, assistiu-se ao desenvolvimento de teorias urbanas assentes na valorização do uso do automóvel na cidade, manifestas na Carta de Atenas, que promoveram a criação de ambientes urbanos com e para o automóvel, transformando assim a imagem das cidades e a forma como o homem vive e se posiciona em meio urbano. Embora a alteração da paisagem urbana não se deva exclusivamente aos veículos motorizados (é preciso lembrar que o êxodo rural para as cidades, o consequente aumento exponencial da população e a necessidade de expandir para território rural fora do centro urbano, graças à existência de vias de comunicação que permitem o rápido acesso ao centro, são variáveis importantes para a compreensão do problema), ele é um dos responsáveis pela forma como o homem vive na e a Cidade.

Necessidades de vias de comunicação largas e rápidas, lugares de estacionamento, semáforos, sinalética de trânsito, prioridade de deslocação para o automóvel, poluição sonora e da qualidade do ar, alteraram a imagem das cidades e diminuíram as condições para a mobilidade do peão, tornando o caminhar em meio urbano como algo difícil, perigoso, lento, chato, desagradável[4].

Com a introdução dos meios mecanizados de transporte, a perceção que os sentidos fazem do que os rodeia, a alteração da velocidade com que o homem se desloca na cidade – metro, comboio, automóvel – transforma-a de uma forma intensa. O homem desloca-se a uma velocidade média de 5 km/h, que lhe permite sentir o espaço envolvente, entendê-lo e posicionar-se nele, de uma forma natural e saudável, integrando-se e interagindo com a estrutura arquitetónica, urbana, cultural e social adequadamente, já os sentidos estão biologicamente preparados para atuarem a essa velocidade. Um aumento drástico da mesma, provoca uma mudança na forma como o espaço é entendido e consequentemente reduz a sensação de integração e de interação com o que rodeia o corpo, e da sensação de pertença a esse espaço.

“Ele [o ser humano] tem a necessidade de ver, escutar, tocar, provar e a necessidade de reunir estas perceções num “mundo”.” (Lefebvre, 2012)[3]

No fim do século XX, grande parte das cidades ocidentais reúne, assim, questões associadas à mobilidade rodoviária, que requerem uma resolução drástica, rápida, eficaz, por parte dos decisores políticos – congestionamento, falta de qualidade do ar, falta de estacionamento, insegurança.

Simultaneamente, o fim do século coincide com a possibilidade do fim da era das energias combustíveis com base no petróleo que, a médio prazo, impõe a implementação de um novo paradigma social e económico, que tenha como base uma adaptação a formas de energia renováveis, as energias verdes, a par de uma integração com a lógica colaborativa e de partilha implementada pela Internet[6].

Na alvorada do século XXI, surge assim a grande questão:

– Como tornar as nossas cidades mais sustentáveis e humanizadas, mais próximas de uma escala que seja compreensível e entendida pelo Homem, onde apetece viver, trabalhar, passear?

3. O Caminhar na Cidade, a nova Revolução Urbana

De acordo com as novas teorias de planeamento urbano, há que regressar a uma forma de vida humana mais saudável, sustentável, em equilíbrio com a Natureza. A implementação de mobilidades suaves – usar a bicicleta e caminhar –, parece ser uma das variáveis que, em conjunto com outras medidas que promovam o aumento da qualidade de vida do cidadão urbano, permite solucionar esta complexa equação.

À medida que a sociedade caminha para uma cada vez maior necessidade tecnológica, associada à rede de Internet, a uma partilha de conhecimentos/emoções, ser/fazer e de ligação global[6], o homem urbano promove uma necessidade de regresso a uma essência mais humanizada da cidade, mais próxima das suas necessidades biológicas – integração com a natureza, respirar, andar –, associada a uma vontade de socializar com os pares, que a interação na cidade permite.

Nas últimas décadas, assiste-se a um aumento da preocupação com questões relacionadas com a sustentabilidade, como sejam a reciclagem, a qualidade da comida consumida, a quantidade dos espaços verdes existentes, que nos remetem para uma vontade de conexão com a biosfera, diretamente associada às necessidades biológicas do ser humano, a uma integração mais profunda na natureza, a um regresso à origem, que ficou esquecido depois da Revolução Industrial. Termos como “agricultura biológica”, “produto biodegradável”, “amigo do ambiente” e “energias verdes”, fazem parte do léxico e das questões que preocupam o homem atual, o homem consciencioso, responsável e participativo.

Nesse contexto, as mobilidades suaves, como sejam o andar a pé e o uso da bicicleta, tornam-se prementes nesse homem que se quer colaborativo, conectado, saudável, desportista e preocupado com as questões ambientais. Enquanto a bicicleta como forma de deslocação em meio urbano, começa a ser uma opção em muitas cidades, promovendo uma integração com outros meios de transporte – um grande número de cidades implementou, ou tem na sua agenda, a criação de redes de bikesharing em pontos-chave e implementou uma rede de ciclovias -, muitos centros urbanos começam a preocupar-se com a reorganização do espaço público, por forma a dotarem as cidades de condições de acessibilidade para os peões.

“Our feet reclaim the ground” (Stoll, 2016), é o título deste ensaio e o grito de revolta do homem urbano que não se sente confortável no seu próprio habitat e na sua necessidade primordial de íandar, pôr um pé em frente do outro, balançar o corpo para a frente, sentir o seu ritmo, o batimento cardíaco, a respiração, o oxigénio, a mente solta, leve, os sentidos alerta e despertos para as sensações que o meio que o rodeia promove.

Andar é o primeiro grande salto no crescimento do homem, o primeiro marco da sua vida após o nascimento. Quem se esquece da emoção dos primeiros passos de uma criança? O momento em que larga a segurança dos braços dos pais e se lança sozinho no desconhecido? Como pode o Homem esquecer que andar lhe é tão essencial?

“Walking is the beginning, the starting point. Man was created to walk, and all of life’s events large and small develop when we walk among other people. Life in all its diversity unfolds before us when we are on foot.” (Gehl, 2010)[4]

A importância biológica para o homem que se diz sapiens de usar o corpo, nomeadamente andando, é fundamental para manter uma saúde física e mental. No entanto, e tal como refere Rebecca Solnit[8], com a industrialização, ele deixa de o utilizar para efetuar as tarefas diárias e essenciais como sejam tirar água do poço, arar a terra, transportar pesos, andar, ações que promovem o correto funcionamento do corpo humano, substituindo-se nessas tarefas por máquinas e negando a sua necessidade física. A autora vai mais longe, satirizando com o facto de que simultânea e paradoxalmente, ter que utilizar máquinas de ginásio, para reproduzir esses mesmos gestos no ambiente fechado das fábricas de produção de músculos – os ginásios. É estranho correr nas passadeiras dos ginásios, enquanto se olha para um televisor em frente dos olhos, sem ter como objetivo percorrer um caminho ao ar livre, enquanto se vê a paisagem a passar e se perceciona o ambiente envolvente através dos sentidos, sentindo as estações do ano, as condições climatéricas, os sons, os cheiros, o pavimento percorrido, o pó, a terra, as árvores. Tudo isso substituído por máquinas que põem os músculos a funcionar e nos dizem o que se deve ver ao caminhar nessa passadeira.

O homem do princípio século XXI começa assim a entender que, se quer manter uma qualidade de vida saudável, não basta adotar uma alimentação equilibrada, biológica. Há que ser e seguir a sua própria biologia, e voltar à sua essência física e animal, integrando-se no meio que o rodeia, mesmo que esse regresso ao habitat, seja o regresso ao empedrado urbano, às ruas, às praças, aos parques, à beira-rio (ou mar), às vias arborizadas, ao contacto direto com os outros elementos da sua espécie. Tão essencial como sentir o corpo, é socializar e que melhor sítio para o fazer do que a cidade?

“O direito à cidade não se pode conceber como um simples direito de visita ou de regresso às cidades tradicionais. Ele só pode formular-se como direito à vida urbana, transformada e renovada.” (Lefebvre, 2012)[3]

4. Conclusões

É inquestionável que a Revolução Industrial transformou para sempre a face da Terra, contribuindo para uma alteração dos métodos de produção e manufatura e reescrevendo, dessa forma, a paisagem rural e urbana. A tecnologia alterou, não só o modo como produzimos os nossos artefactos, até então, fabricados manualmente e, consequentemente, em menor número e de uma forma mais lenta, mas principalmente, o modo como nos deslocamos na paisagem, como a entendemos, sentimos e vivemos, consequência direta da introdução da velocidade na vida humana.

A Revolução Industrial trouxe para a rotina humana duas novas variáveis interligadas – o tempo e a velocidade – a partir das quais a vida do Homem se rege – o tempo que permite produzir mais e melhor; a velocidade que permite uma deslocação mais rápida no território; o tempo (ou antes a sua falta) que nos impele para uma velocidade que nos faz sentir a paisagem de uma forma diferente.

Os meios mecanizados – o comboio, o automóvel, o avião – substituíram o andar na paisagem. Os 5 km/h do passo humano, foram rapidamente ultrapassados pelos 90 km/h (comboio), 120 km/h (automóvel), 800 km/h (avião)[9], o que implicou uma alteração irremediável na forma como percecionamos a paisagem. Se esta, particularmente a urbana, se alterou radicalmente, assim como o modo como o Homem nela se desloca, é inquestionável que, a forma como é percebida, como os sentidos a entendem, mudou radicalmente.

No início do século XXI, a resolução de parte dos problemas das cidades – poluição, barulho, congestionamento, desertificação dos centros, insegurança – passa por uma implementação de novas formas de mobilidade urbana, principalmente por um incremento nas mobilidades suaves – andar a pé e de bicicleta.

Caminhar possibilita uma perceção e apropriação do espaço urbano, aumentando a utilização do espaço público e a vivência urbana e trazendo população para os centros desertificados. Por outro lado, reduz os níveis de poluição que se vivem na cidade, incrementando a qualidade do ar, diminui o congestionamento viário e a necessidade de criação de lugares de estacionamento, substituindo-os por áreas de permanência e/ou passeios de qualidade para os peões.

O homem necessita biologicamente de utilizar o corpo para atividades físicas que promovam o bem-estar do corpo e da mente. Caminhar é uma forma simples, sem custos e democrática de exercício que deverá ser acessível a todos os cidadãos, através da criação de condições que facilitem e incentivem, não apenas o andar a pé como exercício físico diário, mas principalmente como modo de deslocação diário.

Viver numa cidade ideal, passa por ter acesso a espaços públicos de qualidade, a socializar em comunidade, sem segregação de classe. Ao ser um ato democrático, caminhar permite, incentiva e promove a integração social.

“Our Feet Reclaim The Ground” (Stoll, 2016)[2]

Carla Duarte

[ENG]

Image 1 – Eadweard Muybridge [1]

- Introduction

“It is only ideas gained from walking that have any worth.”—Nietzsche

In a time when urban mobility is debated by city managers, who aim to improve city’s air quality, requalify public space, so it can be properly used by citizens and make residential areas of city centres more attractive, it makes sense to question how can the introduction of cycling and walking, as a means of urban mobility, be an effective solution to solve some of these problems. Therefore, pedestrianism and urban walking, appear as a practical, simple and effective solution for city’s mobility, as well as other urban problems, and as a key element for urban planning and to increase citizens life quality

2. The City and the Car

The technological revolution started in the XIXth Century, with the invention of the steam machine was, undoubtedly, responsible for a deep change in society with direct consequences in the economic, social and cultural level. What started to be a change in the methodology used to produce goods, and in the rural and urban landscapes (due to industrialization and rural exodus to cities), soon became a deep change in the way Man interacts and integrates in, and with, the territory, how he moves through it and how the way he does it, makes him perceive it in a very different way.

Throughout the XXth Century, and embedded in a profound conviction and belief on the abilities and benefits that the revolution, and the way we move, could produce, there was a growth in the development of urban theories based on the enhancement of the use of the vehicle in the city, manifested in the Athens Charter, which promoted urban environments with, and for, cars and changed the image of cities and the way Man lives and interacts in it. Though this change in urban landscape isn’t only due to motor vehicles, it is also responsible for the way Man lives in, and the, City (we mustn’t forget that the rural exodus to cities, the consequent growth of the population and the need to expand to rural territories outside the city centre, as a consequence of railroads and roads that allow a fast access to it, are important variables to understanding the problem).

The need to have wider and faster roads, parking lots, traffic lights and signs, to give priority to cars, the noise pollution and the lack of air quality, modified the way we see cities, as mentioned before, and reduced the conditions for pedestrian mobility, turning walking in urban areas something difficult, dangerous, slow, boring and disagreeable[2].

With the introduction of mechanical means of transport, the perception that senses do of what surrounds it and the change in the speed used by Man to move in the city – underground, train, car –, transforms it in an intense way. Man moves at an average speed of 5 Km/h, allowing him to feel the space around, to understand it and to position in it in a natural and healthy way, integrating and interacting with the architectural, urban, cultural and social structure adequately, since the senses are biologically prepared to act at that speed. A drastic increase of it, causes a change in the way space is understood and consequently reduces the feeling of integration and interaction with what surrounds the body, and the feeling of belonging to that space.

“He [the human being] as the need to see, ear, touch, taste and the need to gather these feelings in a “world”” (Lefebvre, 2012)[3]

In the end of the XXth Century, the majority of western cities assembles questions linked with car mobility that require drastic, fast, effective solutions by decision makers – traffic jam, lack of air quality, lack of parking lots, insecurity.

Simultaneously, the end of the century brings together the possibility of the end of fuel energy based in oil that, in a medium term, requires the implementation of a new social and economic paradigm, based on new green energies and a new social collaborative and sharing approach, internet based[6].

In the start of the XXIth Century, a big issue emerges:

- How to turn cities more sustainable an humanized, closer to a scale that understood by Man, where he wants to live, work and walk?

3. Walk in the City, the New Urban Revolution

According to the new theories of urban planning, Man must return to a healthier, more sustainable and nature balanced way of life. The implementation of healthier mobilities – cycling and walking –, seems to be one of the measures that, amongst others that promote the increase of the urban citizen’s life quality, might solve this complex equation.

As society evolves into a wider technological necessity, linked to Internet, to a share of knowledge/emotions, be/do and of global connection3, urban man promotes the need to return to a more humanized essence of city, closer to his own biological needs – integration with nature, breathing, walking -, along with a will to socialize with its peers, that urban interaction allows.

During the last decades, there has been an increased concern with matters related with sustainability, such as recycling, food quality, the amount of green spaces, referring to a will to reconnect with the biosphere, directly linked with the biological needs of the human being, a deeper connection in nature, a return to the origins, that was forgotten after the Industrial Revolution. Expression such as “organic farming”, “biodegradable product”, “environmentally friendly” and “green energies”, are part of every day’s lexicon and some of the questions that concern nowadays man, a conscientious, responsible and participating man.

In this context, walking and cycling become essential to a man who is collaborative, connected, healthy, sportsman and environmental concerned. While cycling as a means to move around urban areas, is a option in many cities, promoting an integration with other means of transport – a large number of cities implemented, or has it on the agenda, creating a network of cycle paths and bikesharing in key points -, many urban centres are starting to concern with reorganizing public space, in order to provide cities with the proper access conditions to pedestrians.

“Our feet reclaim the ground” (Stoll, 2016), is this essays tittle and the cry of revolt of the urban citizen who isn’t comfortable in its own habitat and its own prime need to walk, to put a feet in front of the other, balance the body to the front, feel its rhythm, the beating of the heart, the breathing, the oxygen, the free mind, light, the senses alert and woken to the feelings allowed by the surrounding environment.

Walking is the first big step in man’s growth, the first life goal after birth. Who can forget the emotion felt when watching a child’s first steps? The moment when she lets go of the security of her parents arms and launches into the unknown? How can Man forget that walking is so essential to him?

“Walking is the beginning, the starting point. Man was created to walk, and all of life’s events large and small develop when we walk among other people. Life in all its diversity unfolds before us when we are on foot.” (Gehl, 2010)[4]

The biological importance of using the body for a man who considers himself sapiens, including using it to walk, is fundamental to keep physical and mental health. Nonetheless, such as Rebecca Solnit[8] refers, with industrialization he stops using it to do is daily and essential tasks, such as taking the water of a well, plowing, carry weights, walking, all of these actions that promote a proper functioning of the human body, replacing those with machines and thus denying their physical need. The author goes further, mocking with the fact that simultaneously and paradoxically, he has to use gym machines to reproduce those same gestures inside a muscles production factory – the gyms. It is strange to walk in a treadmill, while looking at a TV screen in front of the eyes, without aiming to walk in open air, while observing the landscape passing by and perceiving the surrounding environment, through senses, feeling the seasons, the climate conditions, the sounds, the smells, the crossed pavement, the dust, the earth, the trees. All that replaced by machines that keep muscles functioning and order what to see while walking along the treadmill.

The man of the beginning of the XXIth Century starts to understand that, in order to maintain a healthy life quality, it’s not enough to have a healthy eating, of organic farming production. He has to follow his own biology and return to his physical and animal origin, integrating in the surrounding environment, even if the return to the habitat, means to return to the stone urban pavement, the streets, the squares, the parks, the riversides (or sea sides), the parkways, the direct contact with the other elements of his specie. As essential as feeling the body, is socializing and what a better place to do it as in the city?

“The right to the city cannot be conceived as a simple right to visit or return to traditional cities. It can only be stated as the right to urban life, transformed and renovated.” (Lefebvre, 2012)[3]

4. Conclusions

It is unquestionable that the Industrial Revolution changed forever the face of Earth, contributing to a variation of the production methods and manufacture and thus re-writing, the urban and rural landscapes. Technology changed, not only the way we produce, until then handmade and, consequently in a lower number and slower way, but mainly the way we move in the landscape, the way we understand, feel and live it and with it, a consequence of the introduction of speed in human life.

The Industrial Revolution brought to the human routine two interconnected variables – time and speed -, through which Man’s life is regulated – the time that allows to produce more and better; the speed that allows a faster movement in the territory; the time (or the lack of it) that forge us to a faster speed that makes us feel the landscape in a very different way.

The mechanical means of transport – the train, the car, the plane -, replaced walking in the landscape. The 5 km/h of the human step, were quickly overcome by 90 km/h (train), 120 km/h (car), 800 km/h (plane)9, which resulted in a hopeless change in the way we perceive the environment. If this, specially the urban, was radicaly altered, as well as the way Man moves in it, it is unquestionable that how it is perceived , how the senses feel it, changed dramatically.

In the beginning of the XXIth Century, the resolution of part of the city’s problems – pollution, noise, traffic jam, lack of population in the centres, insecurity -, can be partly solved by providing cities with new mobility ways – walking and cycling.

Walking allows a perception and appropriation of urban space, increasing the use of public space and urban experience and bringing population to the deserted centres. On the other hand, it reduces the levels of pollution in cities, increasing life quality, reducing the traffic jam and the need to create parking lots, replacing it by standing areas and quality sidewalks for pedestrians.

Man biologicaly needs to use the body for physical activities that promote his body and soul welfare. Walking is a simple, free and democratic way to exercise, that should be accessible to all citizens, through the creation of conditions that ease and encourage, not only walking as a daily exercise, but mainly as a daily travel form.

Living in na ideal city means having access to qualified public space and socialize with the community, without class segregation. As a democratic act, walking allows, encourages and promotes social intregration.

“Our Feet Reclaim The Ground” (Stoll, 2016)[2]

Carla Duarte

[1] http://bootsnburbs.blogspot.pt/2014/04/photographer-eadweard-muybridge.html

[2] Stoll, T. (28 de Março de 2016). The Elephant’s Journey. Obtido de The Elephant’s Journey: https://theelephantsjourney.wordpress.com/2016/03/28/flow-chart/

[3] Lefebvre, H. (2012). O Direito à Cidade. Em H. Lefebvre, O Direito à Cidade (pp. 107-120). Lisboa: Estúdio e Livraria Letra Livre.

[4 Jan Gehl in “Cities for People” mentions that, curiously, the necessity to stop in traffic lights reduces the quality of the experience of walking in the city, and, consequently, the will of the walker to do it.

[5] Lefebvre, H. (2012). O Direito à Cidade. Em H. Lefebvre, O Direito à Cidade (pp. 107-120). Lisboa: Estúdio e Livraria Letra Livre.

[6] Rifkin, J. (2014). A Terceira Revolução Industrial. Lisboa: Bertrand Editora.

[7] Gehl, J. (2010). Cities for People. Washington, Covelo, London: Island Press.

[8] Solnit, R. (2014). Wanderlust A History of Walking. London: Granta Books.

[9] As velocidades foram calculadas de uma forma média, considerando um automóvel em via rápida e um avião em velocidade de cruzeiro. The speeds were estimated considering a car in a highway and a plane in cruise speed.

A year on…

July 2, 2016 § 1 Comment

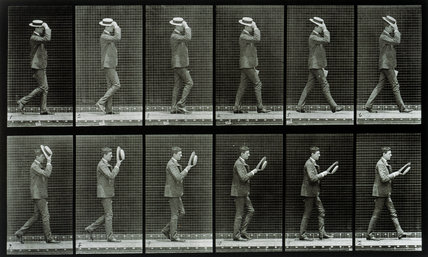

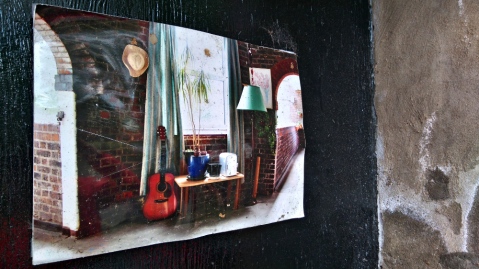

A year ago Gill, John, Carla and I posted our work in Deptford and Greenwich, with Gill experiencing her first urban posting with TEJ. It was soon after my Oxenham House exhibition in Deptford, and after I had given away the exhibition prints to the participants of the project, I was left with the print that was used to signpost people to the show in my flat. Our TEJ walk was the perfect opportunity to repurpose the print and hang it not far from the block where the project took place.

I didn’t expect the print to stay for long as images I had previously posted in that spot disappeared almost instantly (although in one case I’m sure I didn’t use strong enough adhesives – this time I used strong Velcro). But a year later, the image is still there, battered, bruised and covered with a layer of dirt and dust, and with a story of its own. As I walk past this spot frequently, I have been able to watch its movements. About two weeks after posting it, I found the image upside down. It remained in this position for weeks until one day I found it upside up again. This was repeated over some months. Someone was having fun with it – I was amused and eager to pop round to see what it was like that day.

One day this spring, after it had been upside up for some time, I was sad to see that it had disappeared – no remnants on the black canvas, no sign of it on the floor, in or around the spot, nowhere to be found – but knowing this day was inevitably going to happen at some point I smiled thinking about the life it did have and closing the chapter in my head.

Two weeks later I walked past again, not giving the spot any attention but as I turned around from afar for one reason or another (I think it might have been to say Hello to someone I only recognised after walking past) I noticed the image was back again. I immediately returned and marvelled at the new texture of the print: bent, lots of dents, covered in a fine layer of dust and dirt, battered but returned safely from the abyss by a stranger.

I’m curious as to who is having fun with this image – is it one person is it two or more? Why are they engaging with it – did they remove it and return it? Did they find it blown away from the wind and having seen it hanging there before decided to return it? But I also enjoy not knowing who it is and why this is and just being able to speculate about it, asking questions without ever getting the answers and therefore playing with a multiplicity of answers. Perhaps an answer would be disappointing, and so I just keep walking past and watching what is happening. I’m always excited about what I might find.

Anita Strasser

Spring on the Copse 2016

April 27, 2016 § 3 Comments

There has been so much rain in recent months that even the days of sunshine have failed to dry out the ground. The path through the Copse has been almost a sea of slippery mud. Bluebells are beginning to raise their heads but even they look bedraggled at the moment and the strong winds have removed some of the weak branches which have gathered in drifting piles. Sometimes I’ve wondered whether people might have dumped them there over their garden fence.

Two trees were blown down across the path in the recent gales, one of them completely blocking it so that the dogs and I have had to scrabble through some prickly undergrowth to get round it. I had this debate with myself; joggers, dog walkers and families with children do pass through the Copse and the fallen trees are large obstacles. Should nature be allowed to take over or should I phone the Council, who are responsible for the maintenance of this local amenity. I thought about it for a day or so and then decided I would phone as the Copse seemed to be falling in on itself. There was also something in my mind about wanting to prove that people do make use of this small piece of nature, so that there wouldn’t be an attempt to de-label it as green space and make it vulnerable to building development – which has been mooted. I was surprised when the trees were cleared within a week especially as I had agreed with the young man in the parks department that this wasn’t an urgent job. When I say ‘cleared’ I don’t mean completely cleared away but chopped so that there’s a way through.

The other day I was talking with one of the people from a nearby house and we discussed mud, gales, fallen trees and litter on the Copse. The lady said that for quite a while she had cleared the litter but stopped doing that when the Council only started to collect fortnightly and her dustbin got too full. She told me that some young folk have re-built a den again in part of the copse and even installed an old bench. They collect there in the evenings sometimes, lighting fires and making noise. This must have been since a ‘ring’ of branches was laid-out in the area during the Autumn. I wondered about contributing something – maybe I might introduce the bark mask as a decoration. I’ve had some email contact with members of The Elephant’s Journey and when I mentioned this John recalled Stig of the Dump. I’d forgotten Stig but it does fit. I have to acknowledge that I’ve felt a bit of a fraud somehow in relation to The Elephant’s Journey because the other members do their work in urban areas, highlighting adverse developments through their art, whereas I’m out of that loop, working in small green spaces in the suburbs, interacting with what I see. However, John was very encouraging around the idea of a discourse with the den builders.

I’ve also just started to read a lovely book Common Ground (R. Cowen,2015) which is an account of Rob Cowen’s explorations in a nearby edge-land after moving from London to a new home in Yorkshire. He writes, ‘Enmeshed in every urban edge is also the continuous narrative of the subsistence of nature, pragmatic and prosaic, the million things that survive and even thrive in the fringes. This little patch of common ground was precisely that: common. And all the richer for it’ (2015:9) Looking at the illustrated map at the front of the book Cowen’s piece of edge-land is much much larger than mine but I can still notice changes over time and see how nature and people impose their presence. A little further on Cowen writes of entering Chauvet Cave in the Ardeche Gorges and seeing the representations painted and scratched on its walls over between 15,000 and 30,000 years ago and how they show the engagement between animal, land and human. He concludes, ‘What I didn’t realise until later is that in seeking to unlock, discover and make sense of a place, I was invariably doing the same to myself. The portrait was also of me’ (2015:11).

References

Cowen, R. (2016) Common ground. United Kingdom: Windmill Books.

http://bradshawfoundation.com/chauvet/

http://robandleo.com

King, C. and Ardizzone, E. (1963) Stig of the dump. United Kingdom: Puffin Books, Middlesex.

London to Seoul & back

April 5, 2016 § 4 Comments

On Sunday 17th January 2016 a group of photographers met outside New Cross station in South London. They gathered together not far from Goldsmiths College, University of London and it was in Goldsmiths College that this story began.

On Thursday 15th January 2015 two students of photography from Seoul, together with their translator, came to visit John Levett who was a Visiting Research Fellow at the college. They came at the suggestion of their teacher Jiwon-Kim.

Jiwon-Kim had been a contributing member of The London Villages Project of 2011-2012 which had been co-ordinated by John Levett and supported by the members of London Independent Photography.

During the January 2015 meeting between John Levett and the Korean students multiple interpretations of ‘street photography’ were discussed and illustrated. We also took an extended detour of New Cross and Deptford before finishing at the top of Greenwich Park beside the Greenwich Observatory.

We then said good-bye to each other and went our different ways.

And that was it until some months later when John Levett received an email from Bang Sung Wook, one of the students who visited Goldsmiths College. Bang Sung Wok had liked the idea of The London Village’s Project so much that he wanted to create a collaboration on making a ‘Villages Project’ in Seoul and to exchange ideas and images with a group in London.

And so it began …

But first we need to go back …

At the beginning of 2014 the project ‘Bleeding London’ was launched by the photographer and curator Del Barrett. The idea was to photograph every street in London; at least, every street in the London A-Z map of London. John Levett was asked by Del Barrett to co-ordinate the photographing of the edge of the London A-Z map and The Edge Group was born.

The Bleeding London Project was completed in 2015 and was exhibited in London’s City Hall. The Edge Project had it’s own small exhibition at The Greenwich Heritage Museum in Woolwich beside the River Thames in November 2015.

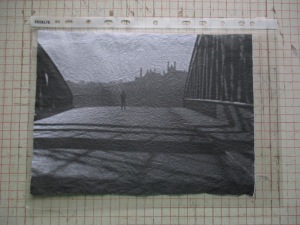

There had been a lot of emailing between Seoul and London and it finished up with the idea of a joint exhibition. The Seoul Villages Project exhibition would also include the images from the London Edge Project and there would be an exhibition of the Seoul Villages Project in London.

So far so good but then another idea came up.

Instead of exhibiting the Seoul images in a gallery space why not exhibit them in the street in the way of The Elephant’s Journey Collective — the idea of using street spaces as ‘A Possible Canvas’; using intrusions into urban spaces as acts of gifting by making the images available for appreciation and, if anyone fancies the image, to appropriate it for themselves. Many images are taken, many are left to decline over time, So far we have never found one that has been defaced or destroyed.

… and so it was that in January 2016 the photographers of The Edge Group came together and populated the streets of New Cross and Deptford with the images of Seoul.

In the spirit of using available free spaces the Korean photographers used former university laboratory rooms for exhibiting the London images.

It is also important that we photographed the preparation of the images and the placing of them in the south London locations. Documenting process is seen by us as part of the practice of art-making. The documentation extends to recording the ‘history’ of the placements. In other words, what becomes of them. These images have been kept as part of an archive of the collaboration.

The photographers in The Edge Group were: Dorota Boisot, Elizabeth Brown, Chris Burke, Gareth Davies, Angela Ford, Roger Ford, Cinnamon Heathcote-Drury, Gordana Johnson, John Levett, Claudia Pilsl, Przemyslaw Polakiewicz, Angela Schooley, Steve Stewart

John Levett

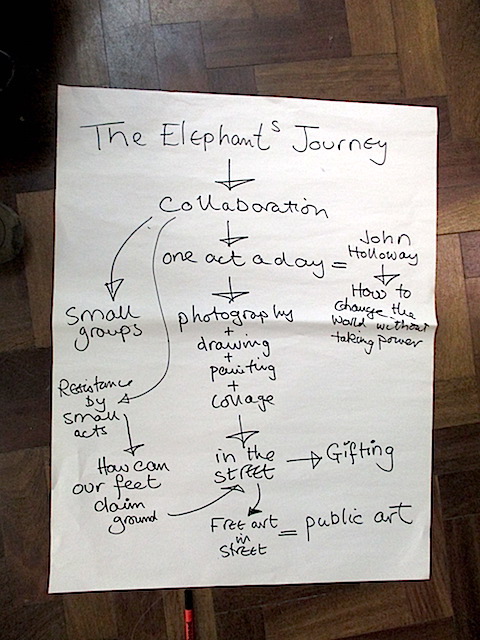

Flow chart

March 28, 2016 § 1 Comment

… from discussions at The Walking-Reading Group in Bethnal Green, London March 2016.

John Levett

Deptford once again

February 21, 2016 § 1 Comment

It seems that there hasn’t been much activity around the Elephant’s Journey. Actually, there hasn’t been much activity in the sense of posting and writing on the blog but perhaps the Journey has moved on, departed from its departure and moved on, moved on towards a transition, not in its meaning and purpose but in the way it is expressed and carried out. It certainly has for me. Hence the inactivity, the need for silence, and now, with having had time to think, the need to write again what it is about…for me.

The Elephant’s Journey has become a dialogue, at times internal, at times external, mostly shared with someone. It has become a continuous and continual dialogue that I have in myself and with myself, and many times shared with others, about what I see, what I experience, what I respond to – in urban spaces. The previous experience of shared walking, talking, reading and posting lingers in my head, as do two books: Geographies of the Absolute and Capitalist Realism. Barely a day goes by where I am not reminded of words, sentences, meanings expressed by their authors. How do we map Capital, how do others map Capital, can we map Capital and who is the message for. The big protective father figure no longer exists, no-one is responsible, no-one to answer for; Capital is visible yet invisible.

Deptford is at the forefront of my thoughts yet again. No surprise I suppose, I live here. And it’s going through some of the most rapacious regeneration schemes in London. It’s Creekside next and all its art studios. If they could have the Crossfields Estate they’d have that too. I respond to others’ responses, wondering why and who, where and what, and what these imply, what they represent. People seem to be reacting to Deptford’s changes, some artistic, some angry, but all mapping the plutocratic capital that’s circulating. Public art is political, it’s social – many share these views. It’s given away by the repetitive nature of the works/scripts, the location, and the act of doing public art as a whole.

Mine is an individual yet social and political response too. Others create public art as members of TEJ have, but now I respond, in my head, by taking photos, by thinking and reading, by sharing with others my responses from others’ public installations. The artist/writer will never know but I respond. This makes me think how others might have responded to our public installations. Do we need to know? Ever since the Enlightenment people have sought for answers, definitive answers. But how can we ever know? How can we ever know how and how many people have responded, what thoughts/dialogues/actions they led to, what impact they’ve had on their lives. But again, do we need to know?

At the moment I prefer to respond to what I see / hear in other people’s responses to what they see and experience. I don’t particularly like what I see in Deptford, maybe because I think I understand the underlying reasons for what I see and experience. Perhaps this form of public art and its responses has succeeded in mapping Capital; maybe that is the reason why I feel uneasy about some of these responses. Many others feel uneasy too…about the reality they speak of…the reality of Deptford, London and the global world.

In the sense of thinking and having a dialogue, at times internal, at times external but mostly shared with someone, there has been a lot of activity…for me.

Anita Strasser

Continuing To develop My Place In Landscape

November 25, 2015 § Leave a comment

We’re well into Autumn now with colours fading, leaves falling from trees and becoming slippery and grimy underfoot. The days are shortening and it’s a time when I start to feel too warm and drowsy to leave my cage and forage outside, but there has been much to do photography wise.

Interventions in the Landscape

Temporary Art

8th October 2015:

I made a flower of leaves under a fallen tree trunk and photographed it.

9th October 2015:

I printed the photograph on 6×4 photo paper and took to the print to lie next to sit original.

18th October 2015:

The leaves had turned brown and were disintegrating but the photograph remained the same.

13th November 2015:

The leaves have disappeared into the drift of dying leaves over the piece of bark.. The photograph is turning in on itself taking on the shape of a small log.

Wild Flower Seed Balls – 15th October 2015

I strewed these on some soil and will wait for them to create their own art and to see what Spring brings.

Pop-up Mini Exhibition – 3rd November 2015

I’ve talked for a while of creating a mini Exhibition where I would hang photographs from trees in the Copse and have received encouraging comments about this from my tutor and also from member of the OCA Thames Valley group. This would be different from creating a piece of work, taking a photograph as record and then leaving the creation to the elements – as Richard Long and Andy Goldsworthy do. Gill Golding sent me a link to the blog of The Elephant’s Journey – a Collective of artists with the purpose “To consider and propose modes of art making and arenas of curation; to work within, what Carla Duarte has described as ‘A Possible Canvas’.

At the heart of our practice is the documentation of our actions. We are at an early stage of what we see as an on-going practice of returning work, derived from the urban sphere, back to its source

Members of the Collective have laid photographs in places in Salford, hung them as mobiles from trees in Lisbon, and Gill placed her work near the O2 in London see here and here. They create their work in urban spaces whereas I create mine in pockets of woodland in suburban spaces. There is something in me that worries about the creation of ‘litter’ in public spaces and I have written about this before. I knew I didn’t want to put something up and leave it there until it disappeared or was taken down and trampled on the ground.

I decided a pop-up Exhibition would be the best for me and, on one of my walks, picked out a spot next to the path which would be easily seen by anyone walking past. Then I printed off four A4 photographs.

The photographs were placed in plastic sleeves, with a green treasury tag through the holes to act as hangers. I had thought of bulldog clips with string as a hanger or dowelling but, in the end, decided that the treasury tags were more simple and in keeping with something very temporary. After further thought I decided to add another plastic sleeve with a sheet labelling the Exhibition and a note adding ”Comments welcome”, plus some scraps of paper and a pencil.

I enjoyed seeing them there. They looked at home somehow and I imagined what it would be like if I was a stranger walking along and saw these photographs in their plastic coats hanging from the trees. Looking closer and thinking, “Oh! They look as if they’ve been taken here”. I went back as it was going dark wondering if anyone at all had seen them as I’ve seen very few people there. They were still there plus someone had actually left a comment. I felt so pleased.

I was going to take them back the next day but it rained and, somehow, I felt that one day had been enough.

Thoughts

I have some doubts about the wildflower seeds. Am I intervening/interfering too much in the environment because I want to see something pretty grow in the Spring and think “I planted those”? Otherwise I feel satisfied with on-going projects so far. It’s good to continue with something and not just to abandon it to make space for the next part of the Module and a new Assignment.

I still have plans for a geo-cache and have been collecting items but I need to think more clearer about the aims of doing this. It needs to be more than a wish to involve myself in creating a ‘treasure’ hunt.

Catherine Banks

15th November 2015

References

https://theelephantsjourney.wordpress.com

The Elephant in Salford

October 13, 2015 § Leave a comment

Once upon a time (and the time was about 1959) the British film industry made a leap. It recognised people who weren’t Robin Hood, Lady Marion, the Count of A B & C, the Duke of etc, numerous generals, admirals & Queen Elizabeth’s. The leap came to land round about 1968 with Lindsay Anderson’s film “If …. (or maybe a few year’s later with Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange).

Anyway …

It was a moment in British cinema when the lives of ‘us’ came to be the content of drama.

The playwright Shelagh Delaney wrote ‘A Taste of Honey’ in 1958. In 1961 the director Tony Richardson produced and directed the screen version.

When planning to travel to Manchester in late September I decided to post-up work derived from stills of the film.

The original play was set in Salford (adjoining Manchester) in the 1950’s and significant parts of the film were located there particularly beside the Liverpool-Manchester ship canal.

I captured some stills (on YouTube) from the film version, ‘treated’ them in the process of creating ‘artefacts’.

I felt that the most appropriate location would be beside the canal. Part of Salford is now referred to as Salford Quays and contains a number of media companies. The other side of the canal has large stretches currently untouched. I felt that if I were to walk both sides then a suitable space to place the images would open up to me. So it was.

On the canal side opposite Salford Quays (part of the outskirts of Manchester known as Trafford Park) I found a space occupied by an installation created to celebrate the history of the wharf there. It came to me as a place into which the work would fit.

I placed the work on an adjoining low wall, photographed the site & left.

I returned the following day & found that two pieces of work had been carefully removed & regretted that I would be unable to return the following day.

Reflecting upon the process: the idea of using stills from the film came to me only a few days before leaving for Manchester & I was highly pleased with the result.

It did, however, raise the question of whether it was completely sympathetic to the space which has been transformed out of any recognition from the scenes of the original film & might suggest a nostalgia for that moment rather than a reflection on the space as it exists or as a recording of a current process of expropriation of land & a distancing of its history.

Cartographies of the Absolute (Toscano & Kinkle) [Cartographies of the Absolute] has been a central text of my consideration of how one records/represents the changes within current neo-capitalist appropriations.

John Levett

Grounding Immobilities: Embodiment, Ephemera, Ecologies Workshop, Lisbon

September 10, 2015 § Leave a comment

The Elephant’s Journey Project presented its work at the Grounding Immobilities: Embodiment, Ephemera, Ecologies Workshop( presented by EASA Anthropology & Mobility Network @ Anthromob), in Lisbon today.

The presentation included some hanging of mobiles outside the auditorium (Instituto de Ciências Sociais de Lisboa),where the workshop took place, so we asked the audience to help us do it, so they could understand a bit of our practice. Unfortunately there was no time to do a proper walking/talking intervention but still they can observe it tomorrow, the second day of the workshop and watch some of it evolution.

Here is the result of the day:

Carla Duarte

The remains of the day

August 26, 2015 § Leave a comment